As Remembrance Day nears, I have been spending time decoding an object that is very precious to me. I inherited my German grandfather’s World War I sketchbook many years ago and immediately loved the cover, with its ties and the word “Sketchbook” in jaunty lettering. I pictured my grandfather Helmuth, an eighteen-year-old bricklayer, purchasing the sketchbook before he left home, unaware of the horrors to come.

Writing for the History Girls blog inspired me to dig out the sketchbook and share a few of the drawings in hopes that readers might be able to shed light on where Helmuth had done his sketching. I began a bit of detective work with the help of the Internet and started to piece together a slim story behind the sketches.

The sketches start in late July 1917 and end in late November. They were not in chronological order so I made a list of them and found that the first sketch, from 27 July, is also the most haunting one of all. The caption translates to “After German air raid”, but there is no location noted. Helmuth must have been someplace with a clear vantage point and enough time to draw this terrifying image.

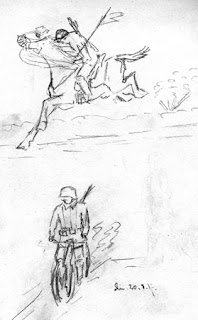

The next sketch is dated 20 August, again with no location. The top image mystified me until I learned that it depicts a rider with an explosion behind him.

There is a gap until early September, when the sketches are marked “Erholung”, which translates to “rest” or “recovery”. The bucolic scenes are empty of people, but seem largely unscathed by war, with one exception. When I discovered that the locations of these drawings (Nonhigny, Harbouey and Gogney) were in the Muerthe and Moselle area of Alsace Lorraine, I wondered whether this was because Helmuth was resting away from the action, behind the German-French border.

There is an infuriating gap after these sketches; the next drawings are dated in November. Helmuth moved from a place called St Loup to Acy Romance and then to the Aisne Canal. The drawings are still well observed but looser and more expressionistic, perhaps a by-product of drawing quickly outside in the cold.

The last drawing in the sketchbook, dated 24 November, of two men by an open fire is hugely poignant to me. They occupy the same space but are separated by an emotional distance, each lost in his thoughts. In silhouette these men could be of any nationality, seeking warmth and solace.

On 11 November I will think of Helmuth, of all those who died and of the survivors whose lives were marred by this war. I will look at the sketchbook and think about how my attitude to it has changed. It is no longer just a collection of landscape drawings but rather my grandfather’s attempt to find some beauty in a war- ravaged land.

If you have any further information or resources you can share with me about the autumn 1917 period of World War I and the Aisnes region, I would be grateful for your comments.

Teresa Flavin is the author of The Blackhope Enigma and The Crimson Shard, published by Templar in the UK and Candlewick Press in the USA.