Among the green hills of Kerry’s Dingle peninsula, by the river in the village of Anascaul, is a neat blue and white pub. The window above the door is home to a pair of large model penguins, and pub itself is called The South Pole Inn.

Among the green hills of Kerry’s Dingle peninsula, by the river in the village of Anascaul, is a neat blue and white pub. The window above the door is home to a pair of large model penguins, and pub itself is called The South Pole Inn. The inn once belonged to my hero, Tom Crean, who was also a hero of three polar expeditions. He travelled to Antarctica with Scott and with Shackleton but his own story was, for many years, almost unknown.

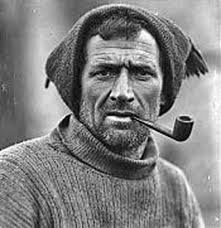

Tom Crean did not belong to a class that wrote letters or diaries for publication. Born in 1887 near Anascaul, he was a poor hill-farmer’s son, the oldest of ten children with little education. After arguing with his father about who let the cow into the potato crop, Crean enlisted in the British Navy at nearby Minard harbour. Aged fifteen, he had to be given a suit by a neighbour before he could set off to Queenstown, Co. Cork, to sail the world and find adventure. Beside the registration of his name are the words “Second Class Boy”.

Nine years later, in Lyttleton Harbour, N.Z., Crean was among a gang sent from The Ringarooma to help another naval ship prepare for a voyage. A troublesome member of that crew had absconded and Able Seaman Crean was selected in his place. His new Captain was Robert Falcon Scott; the naval ice-ship was The Discovery. Crean was sailing for Antarctica, then almost unknown territory. He had found his adventure.

Nine years later, in Lyttleton Harbour, N.Z., Crean was among a gang sent from The Ringarooma to help another naval ship prepare for a voyage. A troublesome member of that crew had absconded and Able Seaman Crean was selected in his place. His new Captain was Robert Falcon Scott; the naval ice-ship was The Discovery. Crean was sailing for Antarctica, then almost unknown territory. He had found his adventure.The Discovery’s 1901 expedition involved exploring and surveying the territory, as well as Scott’s first attempt at the Pole. Crean was involved in laying down supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier and was widely recognised for his enthusiasm, his clumsiness and for his abilities in handling both dogs and horses.

Scott, probably unwisely, believed in manpower rather than animal strength for his sledges. Crean, with a skill developed from his years of pulling the plough, took part in five major sledging trips on this expedition. His own sledge bore the gold harp of the Irish Ensign. On return, Crean was promoted to Petty Officer 1st Class and continued to serve with Scott’s ships. He was reported as “an excellent man, . . . universally liked”.

In June 1910, Crean was part of the crew of Scott’s new ship, the Terra Nova. Galvanised by Shackleton’s attempt at the Pole, Scott was determined to succeed. This time Scott set off with sixteen men, Crean among them, on the 800 mile trip.

At each camp, Scott left some men behind. By the final depot, Crean was one of Scott’s seven remaining men. Stronger and in better shape than the others, he would have hoped to go to the Pole.

At each camp, Scott left some men behind. By the final depot, Crean was one of Scott’s seven remaining men. Stronger and in better shape than the others, he would have hoped to go to the Pole.

It did not happen. Scott avoided telling Crean outright about his decision. Instead, he put his head into Crean’s tent as the constant pipe-smoker cleared his throat.

Scott’s comment was ”You’ve got a bad cold, Crean.”

Crean understood the message.

Bitterly disappointed, he retorted, “I understand a half-sung song, sir.”

Bitterly disappointed, he retorted, “I understand a half-sung song, sir.”

Scott’s choice proved fatal to the expedition. Scott took four men instead of the intended three, making rations short when the men were already in a weak state of health.. He chose Wilson (chief scientist)Bowers (navigator and marine) Captain Oates (army) and the Welshman Taff Evans who had been with Scott on the Discovery. Ever since there have been discussions about his choices. Was Crean not taken because there were increasing concerns about Irish Independence back home, I wonder?

Tom Crean, with Bill Lashly and Lieutenant Teddy Evans, were ordered to return to base camp. The journey back down the Beardmore glacier, with its massive chasms and treacherous ice bridges, was terrifying. By the time they reached the plateau of the Great Ice Shelf, Evans was ill with scurvy, made worse by the meanly calculated rations. Crean and Lashly dumped their surplus gear, put Evans on the sledge and set off again. Evans’ condition worsened, forcing them to stop and put up a tent.

Leaving the weakened Lashly watching over Evans , Crean set off alone on what was a four-day trek. He walked non-stop, through desperate polar weather and with only three biscuits and a small piece of chocolate in his pocket. Crean completed the journey in eighteen hours.

Leaving the weakened Lashly watching over Evans , Crean set off alone on what was a four-day trek. He walked non-stop, through desperate polar weather and with only three biscuits and a small piece of chocolate in his pocket. Crean completed the journey in eighteen hours. Crean was known for his good luck: almost as soon as he arrived at the camp, a blizzard struck. As soon as possible, Crean led the way back to the tent. Lieutenant Evans was in no doubt that Crean had saved his life and, later, Crean and Lashly were awarded the Albert Medal for their actions.

Meanwhile, Scott’s great enterprise had ended in failure. It was Crean, as part of the rescue mission, who opened up the tent-flap and found his Captain lying dead, diary beside him.

The Pole was not done with the Kerryman. In 1914, Crean was on the Endurance with Ernest Shackleton, who wanted to attempt the South Pole from the Atlantic side. The weather remained unusually severe and the Endurance was trapped in the ice.

The men waited and kept themselves busy with their tasks and games.

There was enough time for Sally, one of Crean’s dogs to have a litter of four puppies, and his care of the tiny creatures earned Crean the nickname “mother”.Thye cried for him when he was not around.

Eventually, after fifteen months, the ice crushed the Endurance. The crew were forced to leave and every one of the dogs had to be killed.

Shackleton and his twenty-two men dragged three small boats, the Stancomb Wills, the Dudley Docker and the James Caird, over the shifting ice pack towards the sea. Eventually, with the ice moving treacherously from the swell beneath, they set sail.

Shackleton and his twenty-two men dragged three small boats, the Stancomb Wills, the Dudley Docker and the James Caird, over the shifting ice pack towards the sea. Eventually, with the ice moving treacherously from the swell beneath, they set sail.

Crean was at the tiller of the smallest boat, the Wills. When the navigating officer was to weak to continue, he took over the command. The strong winds and ocean currents took the three boats to the uninhabited Elephant Island, far off the usual shipping lanes and not a place for a long term stay.

Leaving almost all the stores behind with his men on Elephant Island, Shackleton took six men including Tom Crean and Frank Worsley, and set sail in the James Caird, heading for their original destination, the island of South Georgia. The date was 24th April 1914. Far across the seas, the Irish Republicans had launched the Easter Monday Rising.

Miraculously, given the lack of food and water, the size of the waves, the size of the craft – just over 20 foot in length – the James Caird landed on Elephant Island, but not where they had hoped.

Miraculously, given the lack of food and water, the size of the waves, the size of the craft – just over 20 foot in length – the James Caird landed on Elephant Island, but not where they had hoped.The only inhabited place, the whaling station, was on the opposite side of a high uncharted mountain ridge.

Already exhausted, Shackleton, Crean and Worsley set off. It was a distance of thirty miles as the crow flies, but the men had to cross two mountain passes, glaciers, frozen waterfalls and steep descents. Eventually they reached the station and its astonished inhabitants, looking “a terrible trio of scarecrows,” according to Worsley.

Once the other three men on South Georgia were rescued and the James Caird itself brought to safety, efforts were made to reach the men left behind on Elephant Island. Only by the third attempt, with the Chilean vessel the Yelcho, were they successful. According to one source, after all the trio had been through, Crean was the one with enough remaining inner strength to make the authorities understand what was needed and to undertake the rescue.

Shackleton’s remaining men had lived on the beach for almost five months but none were lost. The distance between the pack ice, where they had first set off in the small ships to South Georgia was a voyage of 700 miles in some of the worst seas in the world. “I cannot speak too highly of Crean,” said Shackleton. Crean served in the navy for four more years, his last commanding officer remarking, “An officer of great ability and reliability.”

However, when Tom Crean returned to Anascaul in 1920, he faced a different time and mood. It was dangerous to talk about being part of heroic British adventures. The civil war had arrived and anyone who had worked for the English could end up as a target for nationalist anger. Crean’s own brother Cornelius was murdered for belonging to the Royal Irish Constabulary.

Tom, a quiet man anyway, kept a low profile and refused to answer questions about his exploits. He married, had three daughters, took on a pub and refused Shackleton’s invitation to join the next expedition, saying “I have a long-haired pal now”, meaning his wife, Ellen.

Tom, a quiet man anyway, kept a low profile and refused to answer questions about his exploits. He married, had three daughters, took on a pub and refused Shackleton’s invitation to join the next expedition, saying “I have a long-haired pal now”, meaning his wife, Ellen. Tom Crean settled himself down into ordinary life although he spent little time behind the bar. He loved to walk the hills, glimpsing the surrounding sea, and was simply known as Tom the Pole, a man with a ready smile.

In those days, Dingle was still the back of beyond with poor roads and little in the way of speedy transport. In 1938, when Tom Crean had an attack of appendicitis, there was no surgeon at Tralee.

By the time he was transferred the 70 miles to Cork hospital, it was too late and he died aged 61. Tom Crean's funeral procession was the largest ever seen in the district and he was buried in the family tomb he'd built with his own hands some years before, after the death of his four-year old daughter. Gradually, Tom Crean’s story began to be told more widely, especially in Michael Smith’s book “An Unsung Hero”.

By the time he was transferred the 70 miles to Cork hospital, it was too late and he died aged 61. Tom Crean's funeral procession was the largest ever seen in the district and he was buried in the family tomb he'd built with his own hands some years before, after the death of his four-year old daughter. Gradually, Tom Crean’s story began to be told more widely, especially in Michael Smith’s book “An Unsung Hero”.

It is impossible to give, in this single post, the power of the man and his story. Now, on the green opposite that South Pole Inn, there is a statue of Tom Crean, holding his armful of puppies. In all the reports of him, he is always smiling, joking, hard-working, brave and loyal, occasionally clumsy, an optimist with a terrible singing voice and a great sense of adventure.

On his own, Tom Crean deserves his place in history – and as far more than a "Second Class Boy."

On his own, Tom Crean deserves his place in history – and as far more than a "Second Class Boy."

Yet for me, my hero Tom Crean also stands for the many lesser-known people who have had to leave their homes in Ireland and whose working lives, struggles and untold stories lie behind so many of the great enterprises of the past.

By the way, Tom Crean did end up with some degree of fame. There is a Mount Crean on the map in Antarctica. There is also – and more controversially – the “appearance” of Tom Crean as a great Irish hero in an advert. Not everyone was amused.

My hero's birthday is this coming Thursday, 20th July.

Happy birthday, Tomas O Croidheain

ps I'd also like to recommend "Race for the South Pole, The Expedition Diaries of Scott and Amundsen" in which the writer, Roland Huntford, compares the approach, the planning and the management of both expeditions. Continuum 2010.

Penny Dolan

www.pennydolan.com