Early Orientalist paintings seduce us with their sumptuousness. Women turbaned and bejewelled, lush garments, rooms that glitter with latticed screens filtering the light, stained glass windows casting coloured lozenges across marble floors, fountains, richly patterned Persian carpets, a tame fawn, all suggest the sensuousness of life in the women’s quarters in the Tulip Age.

In the vibrant painting by Jean Baptiste Vanwouw below, depicting a woman’s ‘lying-in’ after the birth of her baby, there’s a sense of sisterhood. A girl prepares a sherbet, another makes coffee, two others pass around incense and rosewater and the woman herself is wrapped in luxurious cloth while others are preparing the baby’s cradle.

But are the paintings a true reflection of life in the harem?

At any given time, Topkapi might have had up to 400 women and children living in its the harem. It was segregated from the rest of the palace by corridors and courtyards and even the girls were segregated by a pecking order. It was presided over by the sultan’s mother – valide sultana – then came the sultan’s sisters, then the four kadins, the official wives, then the girls who had recently caught the sultan’s eye and then the girls he had already slept with. Most famous of these was Roxelana who rose from being a concubine to Sūleyman the Magnificent’s first wife and who managed to persuade her husband to have his oldest son and heir murdered, so that her own son could take the throne.

It couldn’t have been easy to live in harmony. Girls from all parts of the world, with different languages, different customs, dress and eating habits were thrown together, often without the luxury of being able to converse with one another. Some were incredibly young and the large rooms with their stained glass windows and latticed shutters filtering the light must have seemed more like prisons.

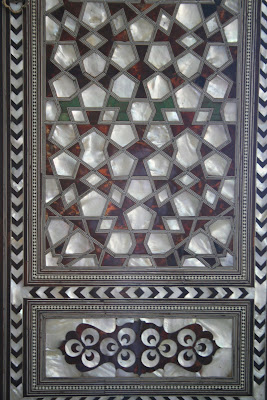

As I strolled through the harem rooms at the Topkapi Palace, I tried to imagine their lives. In the screened, light-filtered rooms with their shimmer of mother of pearl I was looking for ghosts. I imagined how, when they gathered outside in the sunshine in their enclosed courtyards, and caught a glimpse of the Bosphorus, they might have longed to return home to Russia, or Greece or North Africa or wherever.

At any given time, Topkapi might have had up to 400 women and children living in its the harem. It was segregated from the rest of the palace by corridors and courtyards and even the girls were segregated by a pecking order. It was presided over by the sultan’s mother – valide sultana – then came the sultan’s sisters, then the four kadins, the official wives, then the girls who had recently caught the sultan’s eye and then the girls he had already slept with. Most famous of these was Roxelana who rose from being a concubine to Sūleyman the Magnificent’s first wife and who managed to persuade her husband to have his oldest son and heir murdered, so that her own son could take the throne.

It couldn’t have been easy to live in harmony. Girls from all parts of the world, with different languages, different customs, dress and eating habits were thrown together, often without the luxury of being able to converse with one another. Some were incredibly young and the large rooms with their stained glass windows and latticed shutters filtering the light must have seemed more like prisons.

As I strolled through the harem rooms at the Topkapi Palace, I tried to imagine their lives. In the screened, light-filtered rooms with their shimmer of mother of pearl I was looking for ghosts. I imagined how, when they gathered outside in the sunshine in their enclosed courtyards, and caught a glimpse of the Bosphorus, they might have longed to return home to Russia, or Greece or North Africa or wherever.